Over the last few decades, major changes in technology, the way we read and the ephemeral nature of our economies have impacted the way we produce and publish books.

The polarisation of the book industry has become an accepted idea: multinational corporations dominate while small and micro-publishers do well on their own terms as well, with little room for success in the middle space.

This special Writer’s Edit feature will examine what defines large and small publishers, and will analyse the different approaches they take when it comes to signing authors, book production, printing and distribution as well as their approach to marketing and publicity.

We’ll aim explore the diverse environment of book production and bookselling in specific reference to trade publishing.

Defining Big and Small Publishers

In order to examine the different approaches to book production both large and small publishers have, we must first define what ‘large’ and ‘small’ refer to.

Our idea of ‘large’ publishers will be modelled on what are known as the “big six” – Penguin Random House, Harper Collins, Allen & Unwin, Pan Macmillan, Hachette and Simon & Schuster.

These large publishers are major international corporations with multimillion-dollar parent companies such as Bertelsmann, Pearson, News Corp and Lagardère. Small publishers will be defined as those who publish fewer than 30 titles a year and/or earn no more than $50,000 in revenue (Freeth, 2007).

Other significant differences that define these publishers are the number of staff they employ. Large publishers employ hundreds of people from in-house editors, publicists, marketers, and designers to freelancers, while small publishers can operate from someone’s home, with just one or two people at the helm, using largely freelancers and unpaid volunteers.

These details alone portray the vast difference in scale between large and small publishers.

Approaches to Book Production

For the big publishers, the sheer scale of their operations can be immensely beneficial in terms of rationalising and consolidating their economies.

John B. Thompson refers to the “the reduction of overheads and the consolidation of sales forces, warehouses, distribution and other publishing services…” For example, take the results of the recent Penguin Random House merger.

Two initially separate entities, with separate offices, staff and lists are now combining, with the staff from Penguin having just moved into the Random House Head Office in North Sydney.

In addition to tens of thousands of dollars in savings in rental agreements, each department “will be scrutinized for unnecessary duplications. The redundancies will be earmarked for elimination or consolidation” (Curtis, 2012). This is just one example of large-scale consolidation.

Big publishers use one team of experts to produce and sell more books than the small publishing houses, increasing their profit margins considerably. While for small presses producing far less titles, often the owner/founders work ‘day jobs’ to pay the bills, or:

Costs are often kept to a minimum by working from home or renting offices in low-rent premises such as disused factories. If there are paid employees, they often work long hours for modest salaries and much of the routine work is done by unpaid interns (Thompson, 2012).

Although small publishers have less revenue, they can take advantage of the low entry cost into the industry, as well as the virtual office. They have the ability to order, edit and correspond remotely, without the high costs of renting an office space.

One of the most significant factors to identify when considering different approaches to book production is the reputation or ‘brand’ of the publisher. This can affect their approach to book production three-fold: 1. In the quality of staff they can entice and hire, 2. In the prestige of the authors they sign, and 3. In the number of readers and retailers they attract.

When it comes to reputation in book production, big publishers certainly have the advantage. For example, Penguin Random House is a household name in the book world, making it a smart career choice for production professionals and authors.

A certain degree of prestige is associated with big publishers, which is why authors and staff are inclined to work with them over a small publisher. Both staff and authors can expect decent salaries/royalty rates, and may also see a positive effect on their own reputation due to their affiliation with a big publisher.

Readers and retailers must also be considered. As multinational companies tend to dominate the bestseller lists, it’s only natural that both readers and retailers come to associate these companies with books of quality.

Big publishers’ histories are steeped with success stories, and so retailers and readers come to trust their brands. This tells us that big publishers often have the first option when acquiring new titles due to their reputations alone.

Small publishers however, often don’t have the same level of reputation, which can sometimes work against them in terms of acquisition of titles, and indeed, staff.

They don’t have competitive budgets to work with, and so often cannot afford the same services a big publisher can. However, size can work to their advantage when it comes to the economy of favours (Thompson, 2012).

This works in numerous ways, however, the most common being that small presses share their contacts, resources and knowledge with each other, and that freelancers charge small presses far less than they do to a big publisher.

One only needs to look to the local literary magazine scene to see this concept in action. It is particularly evident over social media where publishers like Meanjin, Voiceworks and Griffith REVIEW are all in dialogue with each other, retweeting each others tweets, and answering each other’s questions.

Earlier this year, newly formed Writer’s Edit Press reached out to a number of small publishers including Meanjin, Griffith REVIEW, Fremantle Press, the NSW Writers’ Centre and the South Coast Writers Centre for contributions to help incentivise people to donate to their crowdfunding campaign to fund their debut book Kindling.

Each one of them sent through what they could in the way of subscriptions to their publications, and their latest books. In return, Writer’s Edit Press promoted them on social media, and published profiles of their authors on the Writer’s Edit website.

Similarly, the cover designer for Kindling worked according to the economy of favours rather than her usual rate. By day, Alissa Dinallo designs covers for Penguin Random House however, she took on the brief from Writer’s Edit Press at just a fraction of the cost.

Working for emerging writers is a nice change of pace to working in trade publishing. Even though I love the fast-paced nature and commercial aspects of my job, it’s nice to sit back and get a little more artistic, as well as at the same time, support talented writers who are making a name for themselves (Dinallo, 2014).

Dinallo is in the group of freelancers who, according to Thompson “share the ethos of the indie presses and/or they find it rewarding to do so”. While small publishers can’t throw their weight around when it comes to scale, they can take advantage of the sense of community within the smaller field.

For the most part, large and small publishers use different approaches when it comes to the printing and distributing of books. Large publishers have longstanding relationships with offset printers, warehouses and third party distributors.

Given the sheer volume of business big publishers do with these selected suppliers, the terms are significantly better for them. “Large publishing corporations can put pressure on their key printers to turn around an urgent reprint in three days, whereas a small publisher might have to wait several weeks” (Thompson, 2012).

This means initial quantities of titles can be small, with the flexibility to reprint quickly if necessary. Small publishers cannot afford to operate on this scale.

Small presses feel the pressure of distribution and publicity difficulties far more acutely than publishers in the broader industry because of their lack of resources, both financial and human, and these are usually the make-or-break issues that will decide a small press’s fate (Freeth, 2007).

However, the rise in digital technologies has seen these smaller publishers able to compete without the upfront costs the bigger publishers face. Print-on-Demand (POD) has provided small houses with a much-needed breath of fresh air.

Print on demand is a book distribution method made possible by, and inseparable from, digital printing. It prints books only in response to orders… Due to the capabilities of digital printing, print on demand is capable of filling an order for one book profitably (Friedlander, 2009).

Numerous companies now offer POD services: Createspace, Lightning Source, Lulu, as well as more local printers such as SOS Print + Media, Paradigm and Blurb. However, along with new developments in printing and distribution come changes to book production that affect both big and small publishers: the age of self-publishing and the indie author.

Publishers had the power of the purse and the press… In the world of print, few authors could afford to self-publish… The Internet has changed all that, allowing writers to sell their works directly to readers, bypassing agents and publishers who once were the gatekeepers (Pham, 2010).

This impacts the publishing game in two ways: competition and acquisition. Self-publishing has certainly contributed to the overall sense of ‘doom’ that is currently circulating the publishing world.

According to Fowler and Trachtenberg, “some publishers say that online self-publishing and the entry of newcomers such as Amazon into the market could mark a sea change in publishing” (2010). However, big publishers are now looking to the sales figures of self-published authors to acquire their next titles.

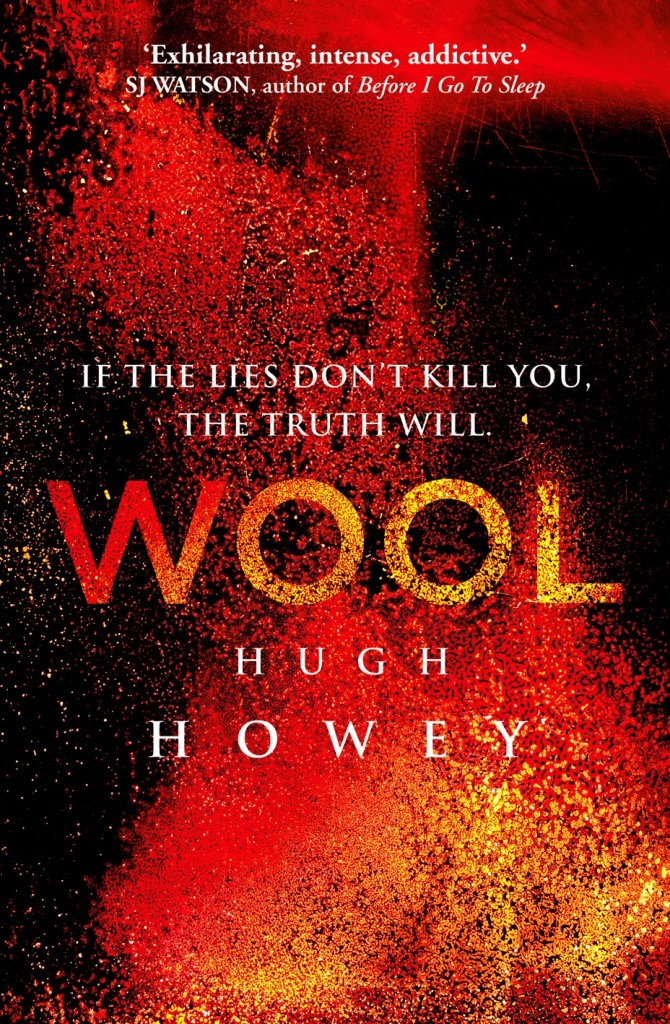

Take the originally self-published author Hugh Howey. Howey published his post-apocalyptic novel Wool through Amazon’s self-publishing services Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) and Createspace. After dominating the bestseller list with his self-published versions,

Howey inked a print-only contract with Simon & Schuster in the US for Wool — released in stores on March 12 of this year — and with Random House in the UK for the trilogy (Anderson, 2013).

This originally self-published author is now set to make both Simon & Schuster, and Random House U.K. a lot of money. However, the varied approaches to book production don’t end here.

Note Howey’s ‘print-only’ contract. Howey controls and maintains the e-book rights to all his books, ensuring that he still brings in revenue independent from the big publishers he’s signed with, and he’s not the only one:

Earlier this year, suspense master Stephen King, Brazilian novelist Paulo Coelho and Stephen Covey, the author of bestselling self-help books, self-published some of their works exclusively on Amazon’s Kindle bookstore (Pham, 2010).

Although hybrid authors like Howey tend to go with the big publishers when they cross over into traditional publishing, the benefits of POD and digital technologies have made a positive impact on small publishers.

According to Thompson, “the rise of the internet also made it much easier for publishers to work with suppliers in India and the Far East, which reduced costs still further” (Thompson, 2012). Furthermore, as the SPUNC report states: “Several publishers have moved to a Print on Demand (PoD) model to reduce costs and keep titles in print” (Freeth, 2007. p. 9).

Financial risk is something that influences the editorial choices of both big and small publishers alike. However, big publishers have far more pressure on them to bring in revenue in order to pay their many staff, authors and printers.

This means they are far more unlikely to risk taking on unsolicited manuscripts. To combat this however, both Allen & Unwin and Pan Macmillan run special programs for sifting through the unsolicited slush pile and acquiring titles by new authors: the Friday Pitch and Manuscript Mondays.

Nevertheless, big publishers must still meet the demands and expectations of their loyal readers. This means producing the regular bestseller titles per year, generally in time for the big three calendar events: Christmas, Mother’s Day and Father’s Day.

The bestsellers on the New York Times Christmas list for 2013 were Stephen King, James Patterson and Nicholas Sparks; names that reoccur every year, meaning there is less diversity in the big publishers’ output. They must also find answers to the latest trends, for example: The Hunger Games trilogy called for the Divergent trilogy and The Maze Runner.

Unlike the big fish, small publishers have more freedom. According to Thompson:

Most small presses tend to be strongly editorially driven and to publish books about which the founder-owner(s) feel passionate… commercial success is generally a secondary concern [that] gives the small presses a leeway to experiment with… in a way that the large houses are less likely to do (Thompson, 2012).

Freeth (2007) notes the value of small publishers:

In general we believe that small press is flexible and has the opportunity to present new or under-represented kinds of writing to audiences… With big publishers being more cautious, there’s a huge role for small and independent publishers, who can use events, use the community, use launches and small publisher models.

Where big publishers churn out similar titles every year at number one on the bestseller charts, small publishers take more risk with the titles they acquire as they run on passion over profit. It is with these risks that small publishers can compete alongside large publishers for literary awards.

Approaches to Marketing and Publicity

Traditional marketing has changed immensely in recent years due to the rise of the Internet and the digital-savvy consumer.

The birth of the EDM (electronic direct mail), banner ads on websites and of course, social media have meant that marketing and publicity operate on a whole new level for both big and small publishers.

However, alongside these developments, one change is quite clear: much of the book marketing grunt work now falls to the author, as budgets for promotion are increasingly limited.

Authors are expected to build an author platform (website) where they can share and promote their work with a target readership they’ve built online. They are also expected to manage social media pages and attend promotional events.

Another change to the marketing and publicity of books is the decline of book coverage in traditional print media. Traditionally in newspapers and magazines, there was quite extensive coverage on books, however:

Even the New York Times, which is one of the few metropolitan newspapers in the US to have retained a stand-alone Book Review section, has shrunk the size by nearly half, from the 44 pages it averaged in the mid-1980s to the 24-28 pages it typically has today (Thompson, 2012).

Because of this decline in traditional coverage, many marketing managers are turning their attention to the online space. According to Coronel, “Books will be made successful by appealing directly to communities of readers online” (2013).

Email subscriber lists and EDMs are a major part of this strategy. This unfortunately works in favour of the large publishing houses.

Consumers recognise their brand far more easily than a small publisher, and are far more likely to offer up their personal data (email addresses) to a widely trusted brand than a newcomer.

Big publishers have had the budget to build up their subscriber lists for years, and so now when they release a new title, or an event approaches, they have an instant target market/audience of thousands.

EDMs, along with online ads placed on their high traffic websites also provide the big publishers with insightful analytics that print never offered. Through these purchased third party services, the marketers from big publishers can determine things like unique visits, impressions, page views, click through rates (CTRs) and bounce rates.

This allows them to analyse what aspects of their marketing strategies work, and what don’t, meaning that their next campaign can be better informed and more effective.

Similarly, big publishers generally have a significant following on social media. For example, Random House Books Australia has 110,066 likes on Facebook and over 22,000 followers on Twitter (official Random House Australia Facebook & Twitter pages).

This means that on just two social media pages alone, Random House Australia has a potential reach of over 130,000 consumers. Unfortunately, the likes of small publisher like Odyssey for example, with just 1,300 followers on Twitter, simply cannot compete in this numbers game.

Freeth (2007) reports:

A lack of resources (both financial and human) mean they often cannot put the necessary time and energy into publicity and marketing that a successful campaign requires.

In regards to publicity in retail, big publishers have to purchase store space and high visibility spots with leading retailers like Dymocks in Australia and Barnes and Noble (U.S.). According to Thompson:

The large publishers also have the resources you need to achieve high levels of visibility within the key retail chains… the larger the publisher is, the more easily they will be able to absorb these promotional costs (2012).

Alternatively, small publishers rely on the economy of favours, hoping that both independent bookstores and the larger retail chains will support independent presses with decent in store positioning.

Finally, a big aspect of marketing and publicity strategies for both big and small publishers is participating in numerous writers’ festivals, literary festivals and book fairs that occur throughout each year.

Publishers attempt to get their authors on discussion panels, at book signings and interviews to gain exposure for their titles. However, one recent strategy combined both online efforts and the buzz of this year’s Sydney Writers Festival.

This event was the first National Book Bloggers Forum hosted by Penguin Random House. Marketing and Publicity Director, Brett Osmond said:

The National Book Bloggers Forum will be a collaboration between the growing book blogging community and Penguin Random House – we want to share news about our books and authors with leading bloggers (Random House Australia, 2014).

Random House invited approximately 50 book bloggers from all over Australia to their head office in North Sydney to hear about their upcoming titles.

This was the first event of its kind, and wasn’t without agenda. Bloggers were encouraged to use social media throughout the day, hashtagging ‘#NBBF14’ and tweeting ‘@RandomHouseAus’.

The result of this was a free social media campaign that lasted over two days. Each blogger was also given a goodie bag containing numerous Penguin Random House titles, which meant numerous book reviews on new release titles circulating online.

Combined, these tactics created much-needed buzz surrounding the PRH brand, and their authors. Valuable connections were also made with Australia’s most prominent book bloggers.

In Conclusion

The polarisation of the book industry is now a widely accepted concept and has led to major changes to the industry that affect both large and small publishers. While this article is by no means inclusive of all the approaches to book production and marketing, various approaches have been analysed – from acquisition to promotion.

With the support of numerous sources, this special feature has also examined the differences in approach to printing and distribution between large and small publishers, explored developments in digital technology and what this means for the industry, as well as delved into the various approaches to marketing and publicity.

Book production and bookselling worldwide will continue to change as our technologies develop, and our reading habits adapt.

While there is much speculation regarding the future of publishing, the rise in book producing technologies can only mean one thing: whether the publisher is large or small, the passion for great books is still well and truly alive.

References

- Anderson, P. (2013, September 9). ‘Hybrid Author Hugh Howey on Self vs. Traditional Publishing’. Publishing Perspectives [web log post]. Retrieved from http://publishingperspectives.com/2013/09/hybrid-author-hugh-howey-on-self-vs-traditional-publishing/

- Coronel, T (2013), What Next for the Australian Book Trade? In By the Book? Contemporary Publishing in Australia (pp. 22-28). Clayton, Victoria: Monash University Publishing.

- Curtis, R. (2012, October 29). Who Shall Live and Who Shall Die: What the Random/Penguin Merger Means to You [web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.digitalbookworld.com/2012/who-shall-live-and-who-shall-die-what-the-randompenguin-merger-means-to-you/

- Dinallo, A. (2014, September 15). Our Cover Designer: Alissa Dinallo [web log post/interview]. Retrieved from https://writersedit.com/news-articles/our-cover-designer-alissa-dinallo/

- Freeth, K. (2007). A lovely kind of madness: Small and independent publishing in Australia. In Small Press Underground Networking Community. Retrieved from http://spunc.com.au/about-spn/report-into-small-publishing-in-australia

- Friedlander, J. (2009, December 3). How Print-on-Demand Book Distribution Works, The Book Designer [web log post] Retrieved from http://www.thebookdesigner.com/2009/12/how-print-on-demand-works/

- New York Times Best Sellers Combined Print & E-Book Fiction (2013). The New York Times [web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/best-sellers-books/

- Pham, A. (2010, December 26). ‘Book publishers see their role as gatekeepers shrink’, The LA Times [web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-gatekeepers-20101226-story.html#page=1

- Random House Australia, (2014, April 21). ‘Penguin Random House Australia announces inaugural National Book Bloggers Forum’ [web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.randomhouse.com.au/blog/penguin-random-house-australia-announces-inaugural-national-book-bloggers-forum-2032.aspx

- Thompson, J. (2012). Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-first Century. Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press

Social Media References

- Odyssey Books Twitter: https://twitter.com/OdysseyBooks

- Random House Australia official Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/randomhouseau

- Random House Australia official Twitter: https://twitter.com/randomhouseau

One response to “Book Production & Marketing – What You Need to Know”

Thanks, Helen.

“… it’s only natural that both readers and retailers come to associate these companies with books of quality.”

Unfortunately the big publishers have allowed their standards to slip in recent years, resulting in books with typos and poor formatting. Everyone seems to be in such a rush to publish that they don’t take the time to produce a quality product.