How much do we know, or care, about Afghanistan? It is here that Australia has made its longest and most little-noticed overseas military commitment. Anyone can become reasonably well-informed about it through media coverage, but you would only know about Afghan and NATO death counts, the corrupt government and shifting timelines for military withdrawal.

I don’t mean to suggest that the above things aren’t happening; it doesn’t mean, however, that nothing else is. A kind of indifference is at work here: the salient facts and details are dutifully reported, but the lives of human individuals remain unexamined.

These ideas, I think, go some way in explaining the success of Khaled Hosseini, author of the wonderful novels The Kite Runner, A Thousand Splendid Suns, and most recently, And The Mountains Echoed.

Of course, his novels’ long-standing place on the bestseller lists should also be attributed to Hosseini’s gifts as a storyteller (which are considerable) and the literary tastes of the reading public (which are more creditable than often thought).

I wonder, though, if something more is at work.

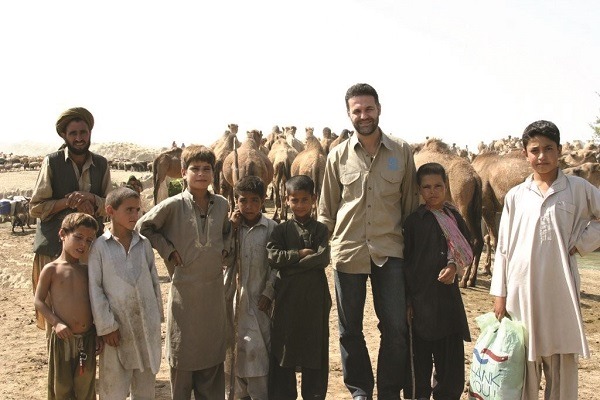

Hosseini brings us the stories about Afghanistan unavailable in the media. Afghanistan ceases to be a place of unfathomable and distant complexity, but a country whose stories seem very near, and both profoundly and ordinarily human.

Hosseini’s themes are familiar and identifiable: grief and guilt; atonement and punishment; the experience of families, fathers and sons, mothers and daughters.

The Kite Runner appeared in 2003, shortly after many in the West had woken up and found themselves supposedly at war in a country that they had forgotten existed. Anyone who looked for and demanded intelligibility in these circumstances would have been well served by Hosseini’s tale of guilt and redemption.

And The Mountains Echoed surpasses Hosseini’s other novels, from a literary standpoint and by its ability to illuminate and make real Afghanistan’s modern history. If you want to know Afghanistan – that is, know more than each day’s revised body count – imaginative literature might just more closely resemble real life.

So then. You want a story and I will tell you one. But just the one. Don’t either of you ask me for more.”

These are a father’s words to his two children, Abdullah and Pari, as they take rest while travelling from their lonesome village to the capital, Kabul. The Father’s story concerns Baba Ayub and his family, and a div – a demon-like creature who descends upon Afghan villages to steal children.

Baba’s family is chosen and he must give up his favourite son, Qais. Wrecked by depression, anger, and the long Afghan drought, Baba departs his village with the goal of hunting the div and reclaiming his son.

Impressed by Baba’s fortitude, the div draws Baba into a pact: Baba can take his son back to the poverty-stricken village where unimaginable hardship awaits, or he can leave Qais with the div, and give him a full chance at a safe and happy life. Choosing the best for his son, Baba leaves, and is never permitted to see Qais again.

Fable and imagination soon become the reality of the novel. The Father relating the story has been beaten by hardship, too:

His eyes looked out on the same world as Mother’s had, and saw only indifference. Endless trial. Father’s world was unsparing. Nothing good came free. Even love. You paid for all things. And if you were poor, suffering was your currency.”

The Mother, in contrast, is kind and bewildered by cruelty, yet the Father’s worldview is vindicated: his wife dies in childbirth before the story begins and, just like the fable, he must soon give up his daughter, Pari, to strangers in Kabul, where a better life might be available.

Hosseini, in a way, gives us ‘just the one’ story, too. The fable mirrors the Father’s story, which echoes and reflects the many different narratives that follow.

Other critics have remarked that And The Mountains Echoed reads more like a series of short stories with central characters merely wandering in and out, but this observation seems to diminish Hosseini’s achievement.

The separation of Pari and Abdullah forms the novel’s centre while myriad other stories and characters intersect and encounter one another, often in surprising and tragic ways. Hosseini skilfully manipulates form and time, and sets his characters’ actions against crucial moments in Afghanistan’s recent history.

Hosseini takes us further back in time, and we meet the sisters Parwana and Masooma, whose separation echoes that of Pari and Abdullah. Another chapter takes the form of a letter written by Nabi, servant to the Wahdati family which took in Pari.

Years and decades turn with the pages, and ordinary life in Kabul is threatened and reshaped throughout the Soviet invasion, the civil war and the rise of the Taliban.

The post-2001 invasion is seen through the eyes of two cousins, as they return to a place which doesn’t resemble home. Another chapter consists of a magazine interview. Hosseini is a master of diverse forms.

These stories, however, are not disparate elements of a grand work. They are the grand work. A number of themes hold together Hosseini’s creation.

First, and most simply, stand the relationships, and what happens when those relationships are broken, rendered impossible, or absent entirely. Pari and Abdullah exist as part of one another and a tangible absence is felt by each during the decades after their separation, even when time has removed memories of the other:

There was in her life the absence of something, or someone, fundamental to her own existence.”

Nila, who adopts Pari, is surrounded by relationships, but only in potentiality; they never give enough meaning to her life, or to others. Pari reflects:

All my life, she gave to me a shovel and said, Fill the holes inside of me.”

Other characters and events bear similar, but no less sorrowful burdens – but I’ll say no more, so that the revelatory moments may belong to you and the characters.

Tragic circumstances put asunder these many relationships, but suffering chooses its victims with casual indifference. It isn’t calculated or divinely mandated. It just is. The decisions individuals make are made with hope, but there is no sure knowledge about their implications.

Markos, a doctor working in Kabul, reflects:

The world didn’t see the inside of you, that it didn’t care about the hopes and dreams, and sorrows, that lay masked behind skin and bone. It was as simple, as absurd, and as cruel, as that.”

These themes parallel and depart from Hosseini’s other works. In The Kite Runner, the kind and gentle Hassan is beaten and raped by thugs, an experience which breaks his friendship with Amir – but not irrevocably, even if redemption arrives late.

Mariam and Laila, the women of A Thousand Splendid Suns, are subject to scarcely imaginable suffering: they apologise for having been born women, Mariam is burdened with seven miscarriages, and for both, suffering is quietly endured.

How unsettling to think that these few lives reflect thousands of real ones, or that many of these characters are the lucky ones, given that they manage to survive. For many, though, death might seem preferable.

In his first two novels, despite what he inflicts upon his characters, Hosseini provides meaningful and satisfying conclusions, which have a paradoxical effect: there is a slight wince at predictability, but also a sense of powerful relief that such a positive resolution did arrive.

Literature and real life may illuminate one another here, too. The Kite Runner landed on bookshelves in 2003, and it helped make Afghanistan intelligible to a public wondering why we were sending our soldiers there.

Hosseini presented us the immiseration of Afghan society under the Taliban, and we sympathised with their victims. Around this time, just like in Hosseini’s stories, an improvement in the lives of the Afghans seemed at least imaginable.

We saw the Taliban on the run, their beaten and broken victims emerging from the ruins ready to rebuild. We saw the return of exiles and refugees, and those amazing images of girls going to school.

But these images faded, replaced with blood and violence as the Western intervention came to look like a mere transition from one painful hardship to another.

These circumstances, I think, must inform And The Mountains Echoed. In contrast to his previous works, Hosseini offers little solace and resolution here. This time, the familiar themes of guilt and sin seem, somehow, inexpiable. He doesn’t give us the endings we expect or want.

The reader, however, is still left much more empowered through Hosseini’s skilful employment of dramatic irony. The reader can look across Hosseini’s creation and see the connections and puzzles that are denied to the characters. The final resolution, scarce though it is, is given to us rather than the characters, the ones who need it most.

The overall effect is a startling and wonderful one. Hosseini fosters an emotional investment in individuals who are both real and imagined. Perhaps this, more than the marvellous storytelling, is Hosseini’s achievement.

When we emerge from his literary world, the newspaper headlines on corruption and uncertainty bear only some resemblance to the real thing, and those commonly employed words like ‘heartbreaking’ and ‘tragic’ come to seem pallid and banal.

Paperback: 448 pages

Publisher: Riverhead Books; Reprint edition (3 June, 2014)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1594632383

ISBN-13: 978-1594632389